Extreme Programming Explained - Book Review

First, this review is a mix between the book’s content and my opinions. I decided to do so because I don’t want to make just one more review that just basically repeat everything the book said, if you wanted to know just what the book is about, you would read the book yourself.

TL;DR

XP is a lightweight, efficient, low-risk, flexible, predictable, scientific, and fun way to develop software. It differs from other methodologies by:

- Its early, concrete, and continuing feedback from short cycles

- It’s an incremental planning approach, which quickly comes up with an overall plan that is expected to evolve through the life of the project

- Its ability to flexibly schedule the implementation of functionality responding to changing business needs.

- Its reliance on automated tests written by programmers and customers to monitor the progress of development, allow the system to evolve, and to ch defects early

- Its reliance on communication, tests, and source code to communicate system structure and intent.

- Its reliance on the design process lasts as long as the system lasts.

- Its reliance on the close collaboration of programmers with ordinary skills.

- Its reliance on practices that work with both the short-term instincts of programmers and the long-term interests of the project.

About the book itself

- Speaks directly.

- Short book, but not because it has lack content, short because it goes directly to the point

- Easy to understand language, none of super complex terms and abstractions. real-world examples.

- It’s very repetitive.

- Excess lists, many of them with the same things.

- Speaks like XP solves all your problems, but we all know that ain’t true.

The book

The code written before you have tested is scary. You never know quite where you stand. Will this change be safe? You’re not sure. As soon as you start writing the tests, the picture changes. You have confidence in the new code. You don’t mind making changes. It’s kind of fun. Shifting between old code and new code is like night and day. You will find yourself avoiding the old code. You have to resist this tendency. The only way to gain control in this situation is to bring all the code forward. Otherwise ugly things will grow in the dark. You will have risks of unknown magnitude. In this situation, it is tempting to try to just go back and write the tests for all the existing code. Don’t do this. Instead, write the tests on demand.

- When you need to add functionality to untested code, write tests for its current functionality first.

- When you need to fix a bug, write a test first.

- When you need to refactor, write tests first. What you will find is that development feels slow at first. You will spend much more time writing tests than you do in normal XP, and you will feel like you make progress on new functionality more slowly than before. However, the parts of the system that you visit all the time, the parts that attract attention and new features, will quickly be thoroughly tested. Soon, the parts of the system that are used most will feel like they were written with XP.

- XP is a lightweight, efficient, low-risk, flexible, predictable, scientific, and fun way to develop software. It differs from other methodologies by:

- Its early, concrete, and continuing feedback from short cycles

- It’s an incremental planning approach, which quickly comes up with an overall plan that is expected to evolve through the life of the project

- Its ability to flexibly schedule the implementation of functionality responding to changing business needs.

- Its reliance on automated tests written by programmers and customers to monitor the progress of development, allow the system to evolve, and catch defects early

- Its reliance on oral communication, tests, and source code to communicate system structure and intent.

- Its reliance on the evolutionary design process that lasts as long as the system lasts.

- Its reliance on the close collaboration of programmers with ordinary skills.

- Its reliance on practices that work with both the short-term instincts of programmers and the long-term interests of the project.

- XP is a discipline, so you NEED to do some things to be doing XP. For example unit tests.

- XP is designed to work on small to medium teams (2 to 10)

- Some of the ideas behind XP are as old as programming, in fact, in the whole software engineering field, most things are very, very old. (very old in terms of software means 40+ years).

Risk: the basic problem

When should I use XP? Use XP when the requirements are vague or changing

Risk is the most basic problem in software development. Some examples of risks are schedule slips for the delivery, the project being canceled, the project has gone so difficult to make changes that the costs of making it doesn’t make sense anymore, defect rate, the software doesn’t solve the problem that was meant to, the business changed, the software features don’t make money, staff turnover and many other you can think of. XP has ways to (partially) solve (almost) all these problems. The speaks in a very clear way about how it would solve all of these problems, but some of them aren’t decisions made by the engineering team, so I don’t think an agile discipline could solve them. But, here are some insights about how XP would solve the problems described above:

- small sprints;

- deliver an MVP first;

- software always in a deliverable state, running tests as possible

- taking a lot of feedback from users, continuously refining specifications during development;

Although I think this makes sense for some problems the author described, this just doesn’t make any sense for the “staff turnover” problem, for example. We work first for money after we choose things we enjoy. Or would you work on your current job for free? I don’t think so. Staff turnovers are mostly because of salary, even though most people won’t admit that because we created a culture where it is “wrong” to say that you just want to earn more money, even though this is the whole point of working.

One good topic is the profits of software. XP can help a lot in this field. As the author says, XP provides you tools to make quick changes, low technical debts, and spend the minimum as possible in the first version, a.k.a. MVP.

I read a good quote about this on Martin Fowler’s blog:

A late change in requirements is a competitive advantage. But to do that you need software that’s designed in a way that’s able to react to that kind of change

Variables of a software

- Cost - Too little and the software won’t be able to solve customer’s problems, and too much too soon creates more problems than it solves

- Time - More time to deliver can improve quality, but the most valuable feedback is feedback from a system in production, so too much time will cause problems. But, too little time and the quality suffers.

- Quality - You can make very short-term gains by not caring about quality, just days or weeks, but the cost — human, business, and technical — is huge.

- Scope - Less scope means better quality. Also lets you deliver sooner and cheaper.

The relationships between them can be complex sometimes. For example, more money doesn’t mean delivery faster. In some cases (in most cases) you don’t need more programmers to deliver software faster. If the quality of your code is a mess, more people working on it may not be a good idea. Maybe, writing tests is what you need. Maybe, your scope is too big, or maybe the time you agreed to deliver this software just isn’t enough because you didn’t speak with anyone technical. Kent Beck is very clear here about Scope is the most important variable. Changing scope, you can manage all other three variables. He provides you with a way of dealing with scope: always finish the most important feature of the release first, so if you need to change the scope and let some other features to the next release, at least the most important one (or, the feature your customers have been asking for the most) is done.

Costs of change

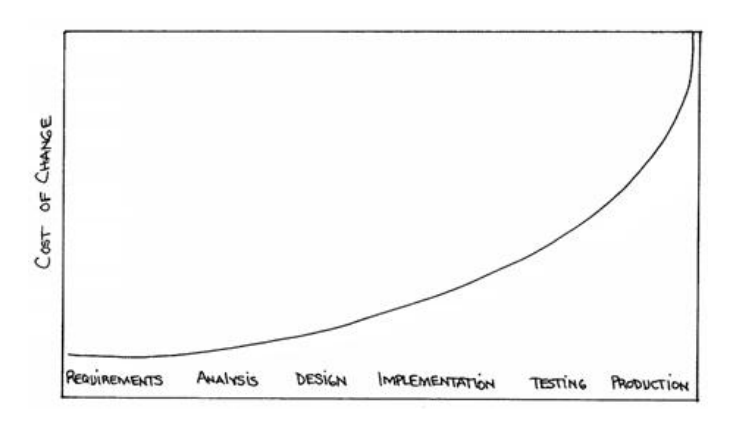

The cost to fix a problem rises exponentially over time. A problem that might take a dollar to fix if you found it during requirement analysis might cost thousands of dollars to fix once the software is in production

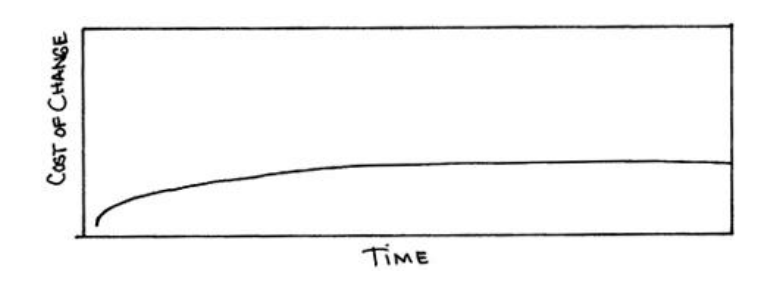

This is a thing almost every software engineer heard of. But the author here says (quite) the opposite. He shows us another image you can see below.

As Kent Beck says, with XP, this is the graph we are looking for. In my opinion, this is completely right. Avoiding changing software in production doesn’t make any sense. You are only going to have true and valid feedback when your software is in production and being used by real people. This is the only time in the software lifecycle that changes are valid. How can you know the decisions you made in the early stages of a software life would be good if you don’t know: who are the customers, what they want, what are their problems, and most importantly, what would they use. It is very common to spend a lot of time creating features that the users simply don’t care about, this is the best way of throwing time and money in the garbage.

Change is the only constant. The problem isn’t change, the problem is the inability to cope with changes when it comes.

The author tells a nice metaphor about driving cars. Driving a car is not pointing in a direction and just going, driving is constantly making corrections to the direction. In software, the drivers are the customers and are the developer’s job to provide the steering wheel to them.

The four values of XP

- Communication - Many problems occur in software development because of communication problems. Managers that punish programmers for telling

the truthand bad news about the project, programmers that don’t tell they’re stuck with a task, people feeling bad about comments in a Pull Request, and many other examples. Another thing about communication in XP is documentation. In XP, it’s more valuable that you have clear tests telling what everything does than a PDF document explaining everything that no one will ever read. The documentation is the code. - Simplicity - This is one of the most important things in software development. Many people think they should do everything for a metaphoric future situation that may never come. Your code should be simple. The simpler it can be. The best line of code is the line of code never written. Less code = fewer bugs. More simplicity = less need for communication. Forget about always designing for reuse. If your code is simple, it would be very easy to add new features in the future.

- Feedback - Feedback is so much more than people telling things. Tests are feedback. Metrics are feedback. Analytics are feedback. They’re all important, but the most important feedback is the one that comes when the software is in production and used by real people.

- Courage - This value only makes sense if you already have the 3 others. Courage is very important for a software engineer. Many engineers don’t dare to delete hundreds of lines of code and start it all again from scratch. But I’m gonna ask you something: how many times you did do this and the code written the second time came worse than the first? We tend to always make it better the second time, so don’t be afraid to throw it in the trash can and start again, because now you have more insights about what works and what doesn’t.

The principles of XP

- Rapid feedback - The time you get feedback (or deliver a change caused by feedback) is critical.

- Assume simplicity - Treat every problem as if it can be solved with ridiculous simplicity. The simpler answers tend to be the right ones.

- Incremental change - Don’t make huge changes all at once, make little changes in every sprint/iteration/deployment.

- Embracing change - The best strategy is the one that preserves the most options while solving your most pressing problem.

- Quality work - Everybody likes to do a good job. This needs to be encouraged by the team.

Some less central principles are: teach learning, small initial investment, play to win, concrete experiments, open and honest communication, working with people’s instincts and not against them, accepted responsibility, local adaption, travel light, and honest measurement. I will not point those out because they speak for themselves and because they’re very (trust me, VERY) repetitive.

The author presents a Back to basics chapter, presenting another list and repeating many things said previously (what a surprise?). The list is about the basic activities of software development (coding, testing, listening, and designing) The ideas about tests are most likely about their importance of them, as the author says:

If you cannot test, it doesn’t exist.

Tests can be unit tests, where programmers know what they just wrote is working, and there are tests specified by customers (a.k.a. use cases) to assert the system as a whole is working. The other items on the list are self-explained.

A quick overview

Just when I thought we were through… guess what? more lists :)

We are presented to the XP practices:

- The planning game - Determine the scope of the next release by combining business priorities and technical estimates.

- Small releases - Put the system into production quickly and release new versions on a very short cycle.

- Metaphor - Guide all development with a simple shared story of how the whole system works.

- Simple design - The system should be designed as simply as possible.

- Testing - (Just the same things we already read about tests… again…)

- Refactoring - Restructure the system without changing its behavior

- Pair programming - All production code is written with two programmers on one machine

- Collective ownership - Anyone can change any code at any time.

- Continuous Integration - Integrate and build the system many times a day.

- 40 hours per week - Work no more than 40 hours a week.

- On-site customer - Include a real, live user on the team, available full-time to answer questions.

- Coding standards - Write all code by rules emphasizing communication through the code.

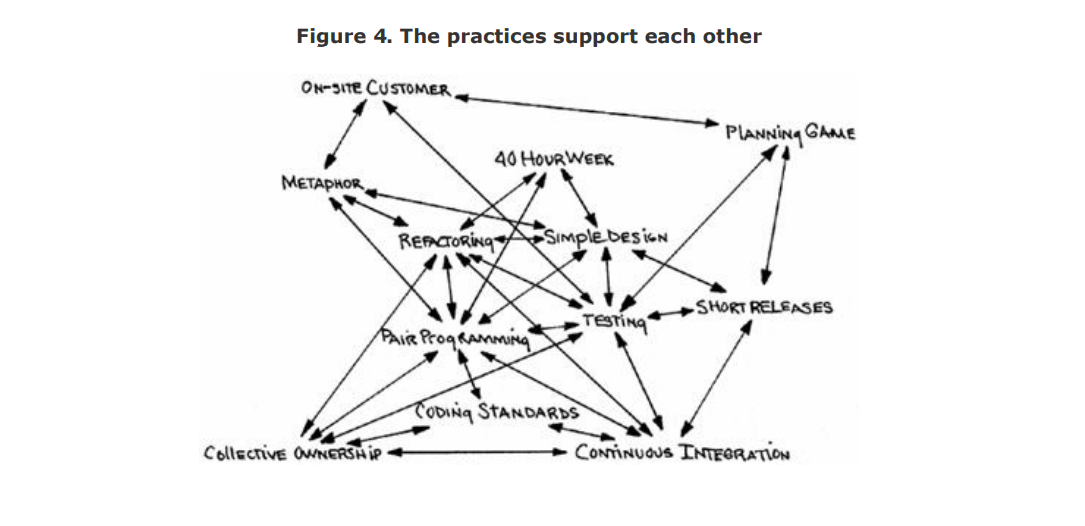

Any practice doesn’t mean anything alone (except for testing), they all support each other. For example, you can only work no more than 40 hours a week because your design is simple. You can only have a simple design because you refactor and test everything. You can only refactor because you test and have continuous integration and so on.

The individual pieces are simple. The richness comes from the interactions of the parts.

Facilities

I found this chapter very interesting. A whole chapter to talk about the facilities of an office, as you can see, this is important for a long, long time ago. We came from a time we had programmers working inside 5m² cubes with no windows (not the OS xD) and sunlight, to now, where we can work from our homes, in a completely controlled environment. Kent Beck talks a lot about how the environment can affect one’s work, providing a cool space, nice desks, nice chairs, expresso machines, toys to play around a little bit to purposely distract yourself from work to clear your mind, public spaces to interact with people and all the things we saw happening in places like Google and Facebook in the early 2010s. I think is cool that Kent is saying that, and my god, he wrote that book in the late 90s, we can’t judge him for anything at that time, but it’s nice to observe some things: they didn’t care about what individuals wanted at that time. Imagine if they arrange their whole office to make people interact a lot, but then comes a new introvert developer. He wouldn’t feel good at all in this environment. I agree with everything Kent Beck said about facilities and I think now, in the 2020s, we have this at a much higher level: working from our homes. At our homes, we can have the environment we want. The introvert can stay in his room all day, the extrovert can go work from a coffee shop or coworking (even go the office on a hybrid model), the one who likes to travel can work while traveling, the one who likes nature can work from a cabin in the woods… Nowadays, you just don’t have any excuse to not work at 100% of your productivity. The fun part is, the majority of companies don’t care about this at all. In the 90s Kent Beck was working with companies that cared a lot about the environment, and in the late 2010s, people were still working at companies with 5m² rooms with not even fresh water or coffee available. We faced a long dark period (which I’m optimistic is about to end) where companies treated workers like they were just robots typing. I see a lot of companies, even small ones, offering a cool, encouraging, inspiring, and diverse environment to workers nowadays, and remote work is the supreme level of this. Nothing is more inspiring than not having to spend 1h a day commuting to work :). They knew about this in the 90s, and even earlier, so, if you still don’t control your environment to inspire your work, I think it is time for you to do so. It changes lives, trust me.

Splitting Business and Technical Responsibility

One key to our strategy is to keep technical people focused on technical problems and business people focused on business problems. The project must be driven by business decisions, but the business decisions must be informed by technical decisions about cost and risk.

This chapter is very good. The author brings up the idea of splitting responsibilities. How painful it is to work on a team where everything is a business-driven decision? “I want this NOW”, “I want that for NEXT WEEK”, and “I want these 5 more features in our scope without changing our deadlines, no choice” are common phrases I already heard from those people. But the author points out very well that, the opposite is also a mess, fully development-driven projects can be even worse, I think. These responsibilities have a very fragile balance between them. Business people need to understand that not everything is possible to do, and engineering people need to understand that deadlines are very important to a business. Not a single decision should be taken by only one of them, everything needs to be discussed by the two.

Planning strategy

We will plan by quickly making an overall plan, then refining it further and further on shorter and shorter time horizons—years, months, weeks, and days. We will make the plan quickly and cheaply, so there will be little inertia when we must change it.

It is nice to see how planning was made some decades ago. The author added some pictures of their plans and the cards were CARDS. Made of paper. We got so used to the idea of panning iterations and sprints on software that I didn’t think that someday, we used to make this on paper.

In the dynamic of panning in XP business people participate among programmers and I think it is a huge difference from planning where there are just technical people. Some decisions need to be made in this step and if made together with the business people, both sides can agree.

The planning cards are divided by risk, priority, and much other relevant information. This gives the team a very clear vision of everything. What to focus on; what to pay attention to; what would be easy and fast do to, etc.

I appreciate this kind of dynamic where you give to the programmers a lot of self-management and let them take responsibility. This adds up to a lot of maturities for the team.

Development strategy

Unlike the management strategy, the development strategy is a radical departure from conventional wisdom—we will carefully craft a solution for today’s problem today, and trust that we will be able to solve tomorrow’s problem tomorrow.

Here there are no secrets, everything we have already covered:

- everything must be integrated into CI

- tests must run 100%

- we should have collective ownership

- anyone can change any piece of code at any time

- without tests this would be impossible

- this makes complex code live much less than usual because many people are going to look at it.

- and because of tests, everyone feels secure to refactor it

- pair programming is not watching someone coding and not tutoring

- it is good because different people look at the code in different ways

- sometimes the person typing can’t see the big picture of the system, and here comes the pair.

Design strategy

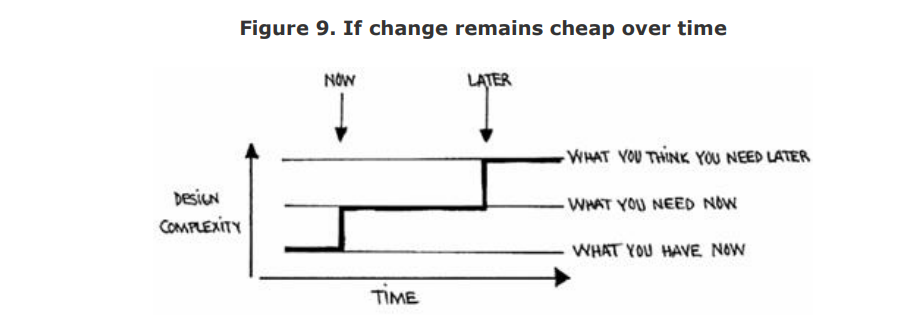

We will continually refine the design of the system, starting from a very simple beginning. We will remove any flexibility that doesn’t prove useful

- all the XP values and principles apply and should be used in the design process

- always have the simplest design that runs the current test suite

- quickly find a way to verify its quality

- feedback on what we learn in the design

- programmers get in the habit of anticipating problems. when they appear later, we’re happy, when they don’t appear, we don’t notice.

- the design strategy will have to go sideways with this “guessing the future” behavior.

- start with a test, so you’ll know when you’re done.

- design and implement just enough to get the tests running.

- if you ever see the chance to make the design simpler, do it.

- by designing this way, the first use only pays what it must.

- the second use pays for flexibility.

- this way, you never pay for flexibility you don’t use, and you tend to make the system flexible only where it needs to be flexible.

What is the simplest design?

Design for today.

- the definition is the simplest design that runs all the test cases, but what do we mean by simplest?

- fewest classes? fewest methods? fewest lines of code? all of these would lead to side-effect problems

- you should chase these four constraints:

- code and tests together must communicate everything you want to communicate

- must contain no duplicate code

- fewest possible classes

- fewest possible methods

- the main goal of the system is to run the tests and communicate what it needs to.

- another way of looking at this process is as erasure. you delete everything that doesn’t have a purpose - either communication or computational. what you are left with is the simplest design that could work.

- instead of reducing the probability and cost of rework, XP goes the opposite way, XP embraces rework, and a day without refactoring is almost like a lost day.

Testing strategy

We will write tests before we code, minute by minute. We will preserve these tests forever, and run them all together frequently. We will also derive tests from the customer’s perspective.

I think it’s very interesting that nowadays, people don’t care so much about tests. I mean, in all the companies I worked for, almost everyone thought about tests as something that is just a “plus”, something that isn’t necessary, isn’t important and we will only have when “we have time”. Every programmer knows that we never have time, so by saying this, it has a strong probability of meaning never. The curious part is that testing is a strongly established practice for decades and the fact that so many people don’t give them the importance they should intrigues me because I can see a tendency of people to think about practices that come from a long time to… old. People always want to update React to the last version, but never want to write tests. People always want to change a REST endpoint to send just the necessary information, removing 3 useless props from the payload and decreasing 1kb from payload size, make a super simple component a microservice, and divide a 50 lines component into 3 more because “having big files is not a good practice” (which is meaningless, by the way) nowadays, but do not want to write tests. Some people forget some things: “old” practices were tested. Not only by people but tested by time. The lifecycle of modern frameworks is very, very small compared to the base of computer science, that’s the difference. The framework you’re using today is probably gonna be garbage in 10 years, testing software is gonna be a good decision as long as software exists.

What to test?

You should only test things that could break. Yes, testing is a bet. Sometimes you just don’t expect something could break, but most of the time, you can. Anything you can do to make your code more predictable is welcome in this case. Let’s think of a Javascript application for example. In an untyped language such as Javascript, it is very hard to know if something can or can’t break. In this case, you would have to write a lot of tests, even though a lot of them are going to be worthless because you’re testing parts of the code that can’t break, but you don’t know that. Now, think of a Typescript application. In Typescript, many of your tests won’t be necessary because the compiler won’t let you even write them. So, make everything you can to help your system to need fewer tests. Besides the usual tests (unit and functional) there are more types of tests:

- Parallel tests - A test designed to prove that the new system works exactly like the old system.

- Stress tests - A test designed to simulate the worst possible load.

- Monkey test - A test designed to make sure the system acts sensibly in the face of nonsensical input.

Implementing XP

Adopt XP one practice at a time, always addressing the most pressing problem for your team. Once that’s no longer your most pressing problem, go on to the next problem.

Thanks to Don Wells for the simple, obviously correct answer to the question of how to adopt XP.

- Pick your worst problem.

- Solve it the XP way.

- When it’s no longer your worst problem, repeat.

Fail fast, learn fast

The first thing to do when trying to change to XP is to test. Without tests, you don’t have the main reason why XP shines: fast feedback. After writing tests (for the right things) you now have confidence in your software and you can deliver things fast and learn fast with customer feedback. But you don’t have to spend weeks just writing tests, you can do it on demand:

- when you need to add a new feature to an untested code, write tests.

- when you need to fix a bug, write tests.

- when you need to refactor, write tests. After writing tests for everything, now you can delete every piece of code you aren’t using now and/or you wrote just to “predict future problems” which can never come. Although the other XP principles are much easier and intuitive to apply, managers can pass through hard times in the beginning. It can be hard to let the programmers make decisions that were once made by the manager and let the customer participate in the whole process.

The author says that pair programming should be the #1 priority in development in the beginning, and he talks about moving desks and putting programmers together. In the 2020s context, I would say this is the time to put all of the company’s worthless articles about how they have a “strong culture” in practice. We see a lot of talks about culture on LinkedIn and a few debates about culture on companies’ channels. It is important to be aware that, if your project is already a mess, XP won’t save you. Applying XP on a good and healthy project can be tough, so you can imagine how hard it would be to apply it on a messy codebase of a failed project.

Lifecycle of an ideal XP project

The ideal XP project goes through a short initial development phase, followed by years of simultaneous production support and refinement, and finally graceful retirement when the project no longer makes sense.

- Exploration - This process consists in exploring the alternatives until the team is confident enough to make estimations and the customer is confident enough that the programmers will understand his needs.

- Planning - This phase is where the programmers and the customer will agree on the release dates and clearly define the scope of the project.

- Iterations to first release - Make one to four weeks iterations, starting with the architecture tasks, and in every new iteration, deliver testable features to the customer.

- Productionizing - Make the final adjustments to shipping your project to production. Now it’s the perfect time to take a good look at performance.

- Maintenance - This is the most common state of a project. Here, we have software in production, but we are still adding new features, fixing bugs, and making breaking changes. Take some time here to make exploration cycles again, try new patterns, and new technology, and make big refactors.

If the customer can’t come up with new stories, we say the project is dead. Now, it is time to write a five to ten-page tour of the system, the document you wish you would find if you need to change something five years from now. The project can die in a good way, where customers simply can’t think of anything new they want because they already have everything they need, or in a bad way, where the system just can’t deliver value.

Roles for people

Like in sports, in XP everyone has to have a well-defined role. Some inexperienced managers sometimes try to change people, but in XP, we reinforce them to just change the role.

Programmers

The programmer is the heart of XP. Without them, none of the other roles would be useful. If programmers were all good at talking, understanding people’s needs, and very communicative, none of the other technical roles would have meaning. But this isn’t true, most of them aren’t good at this (with exceptions, of course). Being a programmer in XP is not so different than in other disciplines, the bigger difference would be things like sharing ownership, testing everything, and trying to simplify everything. As programmers, we all have fears, everybody is afraid:

- of looking dumb

- of being thought useless

- of growing obsolete

- of not being good enough

Without courage, XP just simply doesn’t work.

Customer

The customer is the other half of the essential duality of XP. The programmer knows how to program and the customer knows what to program. The customer in XP needs to write stories and be comfortable influencing a project without being able to control it, and most importantly, the ability to make (hard) decisions.

Tester

The tester helps the customer to think of and write tests.

Tracker

The tracker is the team historian. It comes up with an analysis of the estimations, statistics, and data about the last iteration. The tracker should be able to tell, after two iterations, if the team is going to be able to deliver the software in time. The skill he needs most is the ability to collect information (an easy process nowadays).

Coach

The coach is responsible for the process as a whole. He should be able to think of XP from a big picture, coming up with new ideas of what to do, when to do, or when not to do some XP processes. He should be able to manage people correctly. The need for a coach diminishes as the team matures.

Consultant

Sometimes even in XP, the team can face technical barriers, and in times like these, comes the consultant. It should be very easy for consultants in XP because the team already wrote lots of tests and by them, the consultant can easily understand what are their needs.

Big boss

The boss in an XP project needs to have a lot of courage and confidence in the team. In XP, the team certainly won’t mind telling everything direct to the point with the boss. “if you don’t hire one more person for this certain role, or you need to reduce scope, or postpone the delivery.”. Phrases like that should be common in an XP project, without seeing rude or aggressive, because they’re the truth, so the big boss in an XP project should be able to hear the truth.

The 20-80 rule

The full value of XP will not come until all the practices are in place. Many of the practices can be adopted piecemeal, but their effects will be multiplied when they are in place together.

XP uses this rule a lot. 80% of the benefits come from 20% of the work. You can see this in things like doing the most valuable features (20% of the scope) brings 80% of the benefits. XP can get you better results if you do all of its principles, but this is not a rule. You really can have some of them and still get good results.

What makes XP hard

Even though individual practices can be executed by blue-collar programmers, putting all the pieces together and keeping them together is hard. It is primarily emotions—especially fear—that make XP hard.

The hardest thing about XP is taking responsibility. In an XP team, a person should be responsible for making the estimations about their task, different from SCRUM, where, in most cases, the team makes estimations together about everything. The responsibility is not just about estimations, is for the whole lifecycle of that task.

Although, it can be hard for other reasons too:

- Requires cultural change: XP is a culture shift, where the team and the stakeholders must embrace the philosophy of the methodology. If a team is not ready to embrace the XP values of simplicity, communication, feedback, and courage, it can be difficult to implement.

- Emphasis on pair programming: XP places a strong emphasis on pair programming, which requires developers to work in pairs throughout the development process. This can be challenging for some developers who prefer to work independently.

- Continuous Integration: XP requires continuous integration, where code is integrated into the main branch of the code repository multiple times per day. This requires significant automation and can be challenging to set up and maintain.

- Testing: XP requires extensive automated testing to be written and run continuously, which can be time-consuming and require a lot of effort.

- Emphasis on simplicity: XP values simplicity, but creating simple code is not always easy. Developers must be skilled at identifying the simplest solution to a problem, and then be disciplined in implementing that solution.

- High level of communication: XP relies on a high level of communication between team members and stakeholders. This requires strong communication skills and can be challenging if team members are not used to working in a highly collaborative environment.

When you shouldn’t try XP

The exact limits of XP aren’t clear yet. But some absolute showstoppers prevent XP from working—big teams, distrustful customers, and technology that doesn’t support graceful change.

As the author says above, I’d like to emphasize “technology that doesn’t support change”. Big teams are okay because you always can divide them into smaller teams easily, but technology is always something difficult to change. If you have your processes so much tied up that it takes days and days of tasks to make a simple deployment to production, maybe XP would be so hard for you and would lose the biggest advantage that it wouldn’t make any sense for you.

Some XP principles should be adopted even if you don’t do XP. Testing is ALWAYS a good practice, doesn’t matter the discipline you are into.

XP at work

XP can accommodate the common forms of contract, albeit with slight modifications. Fixed price/fixed scope contracts, in particular, become fixed price/fixed date/roughly fixed scope contracts when run with the Planning Game.

Since XP is so flexible, contracts with fixed dates, scopes, and prices can be hard to manage. Instead of this, XP requires contracts like a type of subscription. It doesn’t make sense to have fixed contracts because you just can’t know if your scope is going to be the best. It is much smarter to have a subscription, so in every iteration, in every planning game, managers can sit with the team to discuss the direction to go, and after getting some feedback from users, it is much more clear to know.